Three Distinct Persons: A new understanding of the Trinity ❖ Introduction

I had previously shown some hesitation about posting about religion or philosophy on my blog because of the fear that I would be ostracized by those I work with. This fear wasn’t unfounded. I had previously had a blog post comparing christian soteriology to a kind of divine proxy here. I’m fairly positive that on discovering the post one of my coworkers started what I perceived to be an irrational campaign of hatred against me, and I had since removed the post. However, on discovering a christian resource group at my company I’ve since learned to rest in the fact that I have just as much right to be authentically myself as anyone else of any other faith tradition, so I’ve restored it today, knowing that it really doesn’t matter what people think of my personal beliefs, they are at the end of the day my own.

However, unfortunately I find myself in the unfortunate position today of ostracizing myself even from my fellow Christians, as what I am about to expound upon may sound, at least at first glance, as being somewhat heterodox. I am no stranger to judgment and hatred, so I will forge ahead knowing that my personal need to share these ideas with the larger world outweighs my priority of being perceived a particular way by any of the tribes I associate with. That’s not really important to me at the end of the day, and I know for those who I chose to emulate, namely Christ, it didn’t matter either.

To those who are of the Christian worldview that may find themselves quick to judge I want to share with you some wisdom from Aristotle which I have found instrumental to my personal growth, understanding of philosophy and even my faith practice in the last year:

“It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it”

Setting the Scene

This journey of discovery for me started in a very personal way with problems with my marriage that have cropped up over the last few years. I will spare you the details, but suffice to say we started to fail to see eye to eye on the fundamental posture that an individual in the world should adopt when living. I found her struggling to be able to let go, and enjoy life to its fullest in a thriving way, as I believed God truly intended for us to be, and she perceived this impulse in me to be erratic, undisciplined and even hedonistic. I’ve since learned on reading “The Cave and the Light” by Arthur Herman (an excellent resource for anyone with any philosophical leaning whatsoever) that this tension is actually more of a philosophical than religious one, going back to the fundamental tension between Plato and Aristotle. Let me explain this a little bit more in detail.

Plato believed the world to be dual in nature, meaning that there is the material world that we know and see, and an invisible, even mathematical world of “forms”, an idealized world of perfection of which everything in the material world is a cheap facsimile of, including ourselves. This more ideal self living in the world of forms which Plato alludes to is in fact largely where we get our notion of a “soul” from (Christians let’s delay arguing about this until later). Aristotle on the other hand, while not dismissing the invisible world of forms thought that the formal nature, or “soul” of a thing was more of an emergent property of those things, that they “came out of” them so to speak, or are born from them, thus are in some ways a result of it. Aristotle goes on to define 4 different types of causes of a thing, one of which is formal, but the fact remains that in spite of this nuance Aristotle understood a thing and its underlying “essence” to be more closely intertwined than Plato. Aristotle thought this way because he profoundly loved the world and found it beautiful and fascinating, being the first scientist in many ways, and in this you can see that he took the first steps towards a more materialistic worldview. However, Aristotle retained the dualistic nature of material at the end of the day distinguishing between essence and matter, but understood those two things to be more closely dependent on each other, i.e. matter was not “mere” matter but was somehow divinely infused. To summarize, you could say Plato was mostly in his own head, whereas Aristotle was in the world.

However, the philosophers that came after Plato and Aristotle didn’t really understand this nuance and so seeing the battle lines drawn went on to double down on this distinction and a result belief systems like epicureanism, which focus on pleasure and worldly experience, and stoicism, which reject pleasure in favor of dwelling on the ideal, were born.

We can’t underestimate the effect that Plato and Aristotle and those divisions amongst early Greek philosophers have had on Christendom. While Plato has won out for the majority of Christendom, finding champions in Augustine, Erasmus and the reformers, namely Calvin, Aristotle also found his champions such as in Thomas Aquinas and Francis of Assisi.

I want to clarify one thing: I’m not interested in arguing whether or not Christendom originated these ways of thinking and Greek philosophy “accidentally” discovered the truth and beauty of God in them, or if the Greeks influenced Christianity. To me that is a moot point and uninteresting to think about.

However, this Platonic and Aristotilian lens on the problem has largely been lost to me in the course of the last year as I have focused single mindedly on one particular champion of Plato, namely in that of Calvin.

Martha Christianity

Back to my marriage, I have believed over the course of the year that a lot of the discord originated from the fact that my wife adopts a strictly Calvinist worldview, a notion that I, in light of this conflict, now found utterly repulsive. Let me expound on why I felt this way a bit without recreating the debate in its entirety.

I call Calvin a platonist, but it’s probably more accurate to say, in my opinion, that he is hyper platonist (but not necessarily neoplatonist). To Calvin, God himself lives in an idealized world of perfection, but that perfection extends to his sovereignty over the material world as well, having a stronger even deterministic control over the world itself. This idea rears its head ultimately in the Calvinist notion of Predestination and Double Predestination, the idea that God statically predetermines before the foundation of the universe who he wishes to save and who he wishes to damn to hell. This notion of God I call hyper-platonist because the divine, which according to Christians is wholly encapsulated by a static and eternal God outside of time itself, is ultimately totally inert to the will of man, and in my opinion the whole thing boils down to complete “divine determinism”. This means that nothing we do, we truly do of our own free will, but is meticulously predetermined and even executed by God himself. Calvinists will argue this point saying that free will is retained, and that we are not God’s puppets, but the argument that I always go back to is that “I have the free will to tie my shoes as a please, let alone such an important decision (in fact the most important decision), to believe that there exists an benevolent creator.” I find the notion that God imposes himself on us in this way utterly repulsive, as though someone coerced to love another person can bring anyone satisfaction in that love whatsoever. The flip side of double predestination is even scarier, and the notion that someone can be damned to eternal torment (the post Dante understanding of hell) in spite of a desire to love God, and that any belief they have is doomed to be disingenuous is a terrifying notion. Why does this notion even exist in the first place? The goal of this idea is to solve the issue of faith vs. works which is prevalent in Protestant vs. Catholic debates centered around the idea of sola fide or “faith alone”. You can see Calvinistic predestination as a type of “doubling down” on the idea of sola fide, saying that even believing itself can be interpreted to be a work of man which would take the glory away from God. This notion never sat right with me.

The analogy that I use is if someone makes a chocolate cake for me and sets it in front of me, then picking up the fork and eating it doesn’t really convey any type of “effort” on my part, the effort was in the person who made the cake. The desire to abolish works in the act of salvation for the individual (and you can see the hyper focus on individual election is where Calvin ultimately loses his way), in order to abolish legalistic mindsets of the faith ultimately implodes on itself in my opinion because the idea is instituted itself in a legalistic way, which ironically institutes a worse form of legalism. I understood this idea better on reading Max Weber’s book “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism”. To clarify, Weber is not a Christian and he is not a communist, in fact he was critical of Marx, but many consider him the father of the discipline of sociology. However, his book noticed something profound which everyone seemed to overlook about the largely Congregationalist communities that founded the United States and how the individual mandate to thrive (in a capitalist way) somehow got confused with the idea of “fruitfulness” in the sense of Calvinistic election. Combine that with the “individualistic” American Spirit and the notion of the American Dream and you produce a divinely mandated enthusiasm for capitalistic endeavor which knows no bounds. Hence, where American society finds itself today. The concept of election though, is I think a misinterpretation, the bible itself doesn’t seem to espouse election to salvation but rather election to Apostleship or possibly sanctification.

However, the ultimate issue I have had with Calvinism, is the arrogant notion that the statically predetermined elect are evidenced of their election by the “fruits” of their life. Psychologically, in my mind this sets up a system of “achievement” oriented Christianity which ironically creates an even more works oriented mindset than what was there before. Christians suddenly find themselves working hard to “Christian” the right way in order to evidence to their fellow church goers that they are indeed one of the absolutely and statically determined elect. If the fruit of your life is the ultimate evidence of your election then I question then whether or not Calvin, by his own criteria was elect, as his Constitutory truly wreaked havoc on the city of Geneva, creating a kind of hell on earth by outlawing things like dancing and even music with severe punishments. As an aspiring musician who believes in the argument for the existence of God that “The music of Bach exists, therefore God exists”, I could never find myself following someone with this mindset, it is flawed at its root.

“This is why the world hates Christianity”, I found myself saying over the course of the year arguing that Calvinism fundamentally bred a type of “Martha” centric congregation, going on a crusade against what I perceived to be “uptight” Christians, leaving a church which claimed to be non-denominational (but mandated all the Church leadership ascribe to High Calvinism), and I still largely find myself in the midst of that crusade today though my perspective has shifted slightly. “If election exists”, I would find myself saying defiantly, “then I chose to believe I am not one of the elect, and I will love God and my neighbor anyway.”

Static God, Dynamic God

It was about a year before this that I had discovered a notion, which I largely dismissed, and knew to be heterodox to the Christian community (and Calvinists especially), of Process theology. This notion takes another tact on God, saying that rather than being static, God is more dynamic in nature, meaning that he changes in response to mankind, and engages in a kind of process of “co-creation” with him rather than constantly imposing his will on the world. The evidence that they use to support this idea is the observation that in the Old Testament God appears to be discovering man, and attempting different things almost scientifically (with little success) in order to reach out to him. This idea sounded fresh and new to me, and seemed to solve a lot of problems, such as the problem of God as the originator of evil posed by Calvinistic determinism, and the problem of free will posed by its twin Arminianism. The only issue with this system of belief however, to an orthodox christian perspective, is that it significantly weakens the “omniscience” of God, to essentially not be able to know the future. There are many variations and nuance on this idea such as alethic omniscience (God knows every variation of what “may” happen), but suffice to say the settled future according to Process Theology sits squarely out of God’s ability for foreknow. This is justified by some process theologians such as Hartshorne by saying God IS in fact omniscient, if you consider his omniscience as applying to actually realized reality, namely things that have already or are currently happening. In effect the world of future possibility isn’t real in the sense that it has not yet happened. This seems to buck the Platonist and Neoplatonist notion that God sits outside of time in a separate sort of dimension looking at time like it were a gigantic diorama flattened out. Rather it places God squarely within time and perhaps to the perspective of orthodox Christian perspective, at its mercy. Does this just make God truly an emergent property of the material world, in the style of Aristotle’s formal cause? On looking at this belief system closer, you could even view this as making God as being born from the material world, rather than its originator.

The Contemplative Mind

It was around this time that I started reading the works of more contemplative Christians like Thomas Merton and even Richard Rohr and found my mind and faith expanded significantly. His book, “The Universal Christ” provocatively named with a word that most Christians (especially Calvinist) loathe tacked on the front of their favorite word, truly changed my life in ways I can’t explain and don’t really care to, especially to more close minded Christians. I found myself almost closing the book several times having come from a more conservative upbringing, but there were things which he said that seemed to transcend the tribal boundaries of our world and even Christendom itself which gave me a more complete notion of Christ, and a year later helped me to recognize in it the old debate between Plato and Aristotle in this context. Rohr espouses a notion of “panentheism”, a word that sounds too close for comfort to “pantheism” which Christians universally deride, for good reason, but his point isn’t without biblical evidence (he cites Colossians 3:11). Basically panentheism is the idea that matter itself is infused with God’s essence, that God isn’t necessarily equal to matter and the visible world (that would be Pantheism), but that part of him is contained within it. Sounds a bit familiar right? This sounds alot like Aristotle’s notion of divinely infused matter. It is intuitively congruent with this impulse in Aristotle, because on reading this book you immediately grasp the same deep and authentic love for the world and admiration and awe for it seen in Aristotle’s work, and it’s no wonder his work is popular particularly in the secular world. This especially makes sense when you consider how the Plato vs. Aristotle conflict from “The Cave and the Light” played after the Reformation. Essentially largely the Protestant world would go on to double down on a Platonic world view, and the secular world would double down on an Aristotelian one, leading to the Enlightenment and scientific revolution. In a sense Rohr and more progressive Catholic circles are befriending the secular world by adopting a more Aristotilian world view.

The only difference between Aristotle’s view of divinely infused matter, and Rohr’s, is that now, according to Rohr, it is infused not with some abstract world of forms devoid of any ethical notions, but the benevolent originator of all things. This turns matter from being better than God, a type of idol, to being good specifically because it contains within it part of God. Francis of Assisi (Rohr being a Franciscan) seems to shine this same light of admiration and deep love for the world around him so we can see that all of these thinkers are on the same wavelength. (Side note: This idea is captured somewhat in the Catholic understanding of transubstantiation of the Eucharist, so Catholics seem to be more in tune with the Aristotilian world view in general). However, its not just in the Catholic church, the Panentheism of Rohr can simply be understood as the indwelling of the spirit and the temple of the individual priesthood in most of the Protestant world as well, a fairly universally embraced concept in the Christian world.

I find Rohr’s notion of a God of love, and not an imperial, detached, abstract and distant Platonic God (as Calvinist ultimately theologically espouse though they argue tirelessly to the contrary) to be more consistent with my intuitive notion of God. I find myself contemplating God, wordlessly in a place of profound peace and admiration for the people around me, for my life and for life itself. I also find Rohr’s notion of focus on Orthopraxy and contemplation to be sorely needed by the Christian community as a lacking expression of the faith which has been driving Christians away from the church (particularly Reformed churches). I found myself doing meditations, like Lectio Divina and contemplation and adoration and drawing a tremendous amount of peace and understanding from them. I wonder to myself if so many Christians get drawn out of the church into New Age ways of thinking because the New Age offers ways of understanding God which was historically present in the church but was surgically removed by Reformers such as Calvin.

I even started to see new ways of interacting with other Christians and people outside of the Christian faith, a way that leads with searching out that divine God in others first and seeking to correct them by some ideal Platonic abstract last. I’m not exaggerating when I say it has changed my life for the better in profound ways, and I now find myself wanting to sit down with others I don’t agree with whatsoever and understand their pain and deepest needs first and how I can serve those needs, before attempting to impose my orthodoxy or correct them in any way. This is what Christ ultimately did when he defended the adulterous woman, and this is how I want to be to everyone I meet.

This new way of seeing God however, was fundamentally at odds with the rest of the conservative Christian community around me. I found myself saying, I want to sit down and understand first, in an Aristotilian fashion, everyone around me and be a mirror of light to them, especially if it took me to interfaith dialogue and ecumenical thinking. However, I still subconsciously said, just not with Calvinists. I justified this by saying that they were in fact the antithesis of the new mindset which I found to encapsulate Christ likeness, but this left me feeling imbalanced and partial. But finally I had a realization which pulled me out of this mindset, and that was on thinking about the concept of the Trinity, and how it could offer a way out of everything that had tied me in knots before.

Weaving the Threads

Here’s where I get excommunicated but that’s ok. What ultimately resolved all these threads for me was thinking about the conspicuous absence of any discussion or expression of the idea of the Holy Spirit amongst Calvinist communities and its prevalence amongst other communities like Pentacostals. For most Reformed Protestants, there is a hierarchy between the different persons of the Trinity and it goes something like this: Christ is most important, second is the Father as being more associated with the Law and Old Testament (and even Judaism), and third and almost completely forgotten is the holy spirit. I will debate you all day about this, but I will still feel from experience that in most Reformed churches this is the way it is. This unbalanced appreciation for the different members of the Godhead always bothered me, and part of me wanted to bring them back into balance. After spending some time going deep on various sources on the trinity, and subsequently finding myself in doubt and confusion about the academic claim of the henotheistic origins of Judaism, oddness of the book of Enoch, the plurality of the Godhead encapsulated in the idea of Elohim, and later prevalence of Yahweh after the exile, I started to dwell on the chronology of the appearance of the Trinity in the Bible. Christianity believes that Christ was the logos (a very Platonic idea) present at the beginning of creation, and that the Spirit was there too, but why is it that according to the bible we materially interacted with the Father, then the Son and then the Son even seemed to usher in the Holy Spirit in a literal sense on his way out of the material world?

The threads all started to come together for me when synthesizing the more dynamic nature of God espoused in belief systems like Process Theology with the static, imperial notion of God espoused by Calvinism. Then the thought cropped into my head suddenly, what if they are BOTH right in a sense?

What if the father IS in fact the static aspect of the Trinity, and he is eternal, unchanging and does predetermine certain aspects of reality? And the Spirit is then the dynamic nature of the Godhead, still eternal but more mutable, which changes and responds to the free will choices of man? Is the dynamic Aristotelian God of process theology or the more universal loving Neoplatonic God espoused by Rohr in fact corresponding to the Holy Spirit? Is the imperial and static, Platonic notion of God in Calvinism in fact God the Father?

When thinking about this, I think about the Christian hymn “How Firm a Foundation”. We think that the best foundation is totally rigid and does not move at all. However, a totally rigid and unchanging foundation is in fact the most brittle . The best foundation has to be slightly flexible to the changing soil conditions, vibrations and tremors of the ground. Skyscrapers are in fact designed to be able to sway several feet at their top so that they don’t simply break apart. Perhaps this flexibility inherent to a strong foundation is provided by the Holy Spirit. Or perhaps even more orthodox, the integration of the free will choices of man in the plan of God, with its inherent imperfection, provides this flexilibility and the rigidity emenating from the Father to the Holy Spirit provides the boundaries or grounding tensility to keep the building together in light of that unpredictability.

If this is the case however, how do you avoid then making these into two totally separate beings altogether, and have a polytheistic faith rather than a monotheistic one? The answer jumped into my mind as quickly as I had stated the question: Christ. If part of God in the Holy Spirit is more flexible and responsive to mankind then how do you reconcile a more eternal static God with this? How do you go from a being that is totally static and eternal to one that is temporally bound and dynamic (encapsulated by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit within man)? What sort of bridge could possibly serve between these two notions? The difference between them, as far as I can tell, is that one allows for the free agency of man, and of creation itself, whereas the other does not. If you are granting man with free will, and according to Christian theology the accompanying inevitability of sin, then how do you account for that loosening of determinism into non-determinism? There seems to have to be a translational aspect of God which essentially accounts for or atones for the existence of free will in the material world. I argue, this translational aspect of God is in fact Christ, both in nature and in a literal sense as he is believed to bridge between, or be a synthesis of the divine and of the created material existence.

Does this make the Trinity into a polytheistic Godhead of three distinct Gods rather than three distinct persons in one? If so then yes, I am heterodox, and honestly i don’t care, but I don’t believe that it does, because I believe that Christ effectively serves as the glue between these two natures of God.

In thinking about Jesus as the rejected stone which becomes the cornerstone in Peter, you immediately bring to mind the fact that the standards of the builders are not being met in Jesus. I take this to mean that Jesus’s nature is tainted with the imperfection of material existence. We know this to be true, but to what end?

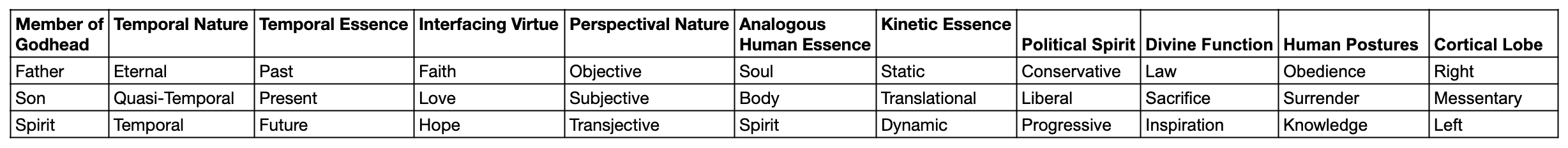

Here I introduce a table that expounds further on these distinct natures of the Trinity and connects them to other notions we are already familiar with, take this with a grain of salt, some of these associations may be unhelpful or misleading. I did however, want to call attention to the idea of Christ as representing the present moment translating between the past represented by the Father and the infinitely possible future represented by the spirit. The idea of Christ corresponding to the present, which is ever dying and being reborn is a beautiful notion which I want to expound on at a later date. Also a shout out to John Vervaeke whom inspired the use of the word “transjective” meaning, translational between Subjective and Objective here.

The Ascendent Triad

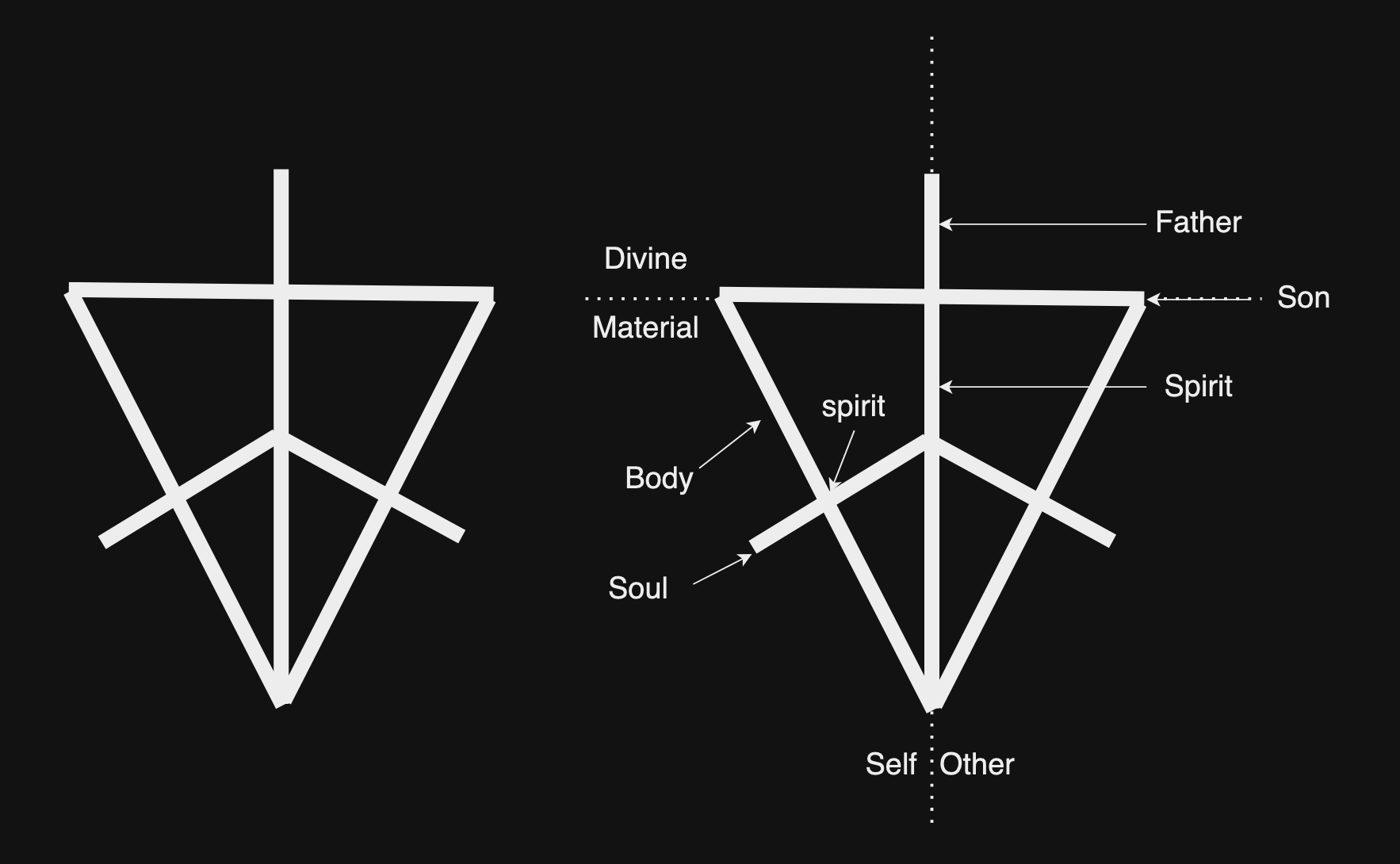

And finally I want to introduce a symbol I invented, and now you are going think i’m really crazy but thats ok too, my favorite people are kind of crazy so I consider it an honor. Before you look at the geometric nature of this symbol and start to jump to the conclusion of Neoplatonic paganism, I want to remind you that a large part of this discussion is a critique of hyper-platonism and platonism in general. This symbol is just a tool to help understand the relationship of the nature of God and the nature of man and it has helped me tremendously:

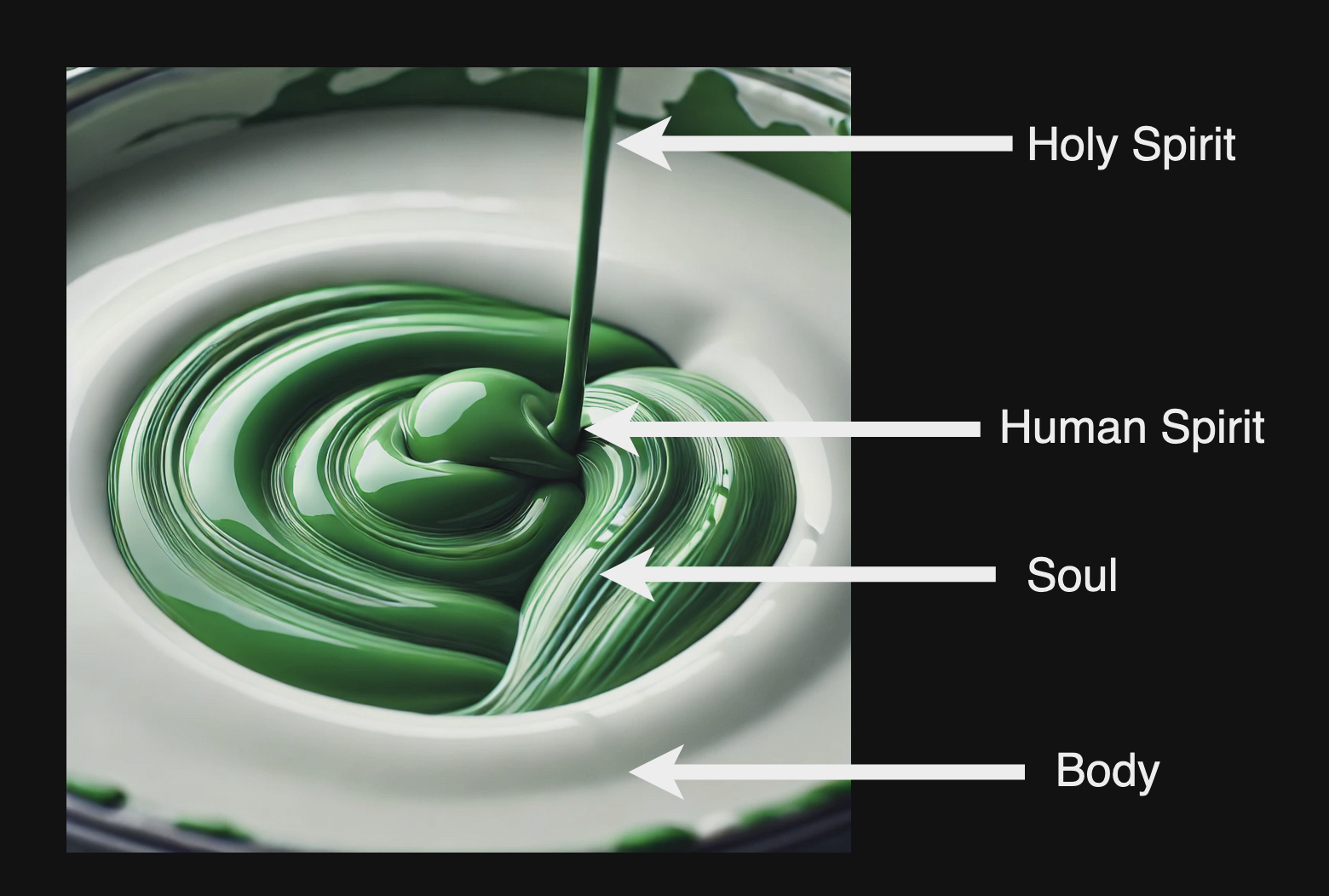

Let me unpack this for you. At the top of this symbol you find the Cross. The vertical beam represents God the Father, emanating down into creation from the eternal plane; you can even think of it as the platonic world of forms if you are of a less Christian persuasion. The horizontal beam represents Christ, and the dividing line between the divine and material existence, and then you see on the other side of Christ an aspect of God extending into creation and then splitting in multiple directions. This I argue is the Holy Spirit, encapsulated in creation, but still inseparably connected to the rest of the Trinity. Why does it split? On the bottom left you see the spirit intersecting another line, I argue this part of the symbol represents the tripartite nature of the individual espoused in Christianity (borrowed largely from Platonism). The line intersecting the beam extending from the Holy Spirit represents the body, or the material aspect of an individual. Where it intersects with the holy spirit is the place of the individual spirit of that individual (or believer if you are being more orthodox and exclusive about how you view it). The beam extending out the other side parallel with the spirit is the Soul.

Think of it this way, the spirit is like a stream of colored paint falling into a vat of white paint which corresponds to the body. Where it hits is the human spirit and then where the paint spreads into a bubble of color occupying the individual’s material existence, we call this region of the paint or body in this analogy the Soul. This diagram shows that man has three natures but what its really trying to convey is that man, or at least sanctified man, appears to have three natures, but on second glance you realize that he actually contains a bipartite nature, and as far as natures that are uniquely his own, he is a simple unity, just a body. The goal therefore of sanctification is to diminish the line extending below the diagram, leaving nothing but body and spirit, aligning yourself wholly with the will of God by means of replacing the will of the soul with the will of the Spirit.

This is where I agree with Merton and Rohr in thinking Buddhist orthopraxy benefits Christianity (particularly so-called non-religious Buddhism such as Zen), in that its goal is to rid the self of the ego. The only difference is that in Christianity the goal of abolishing the ego (or soul as understood in this diagram), is not to escape suffering (Samsara), no in fact suffering is instrumental to that process, however it is not as many Platonist Christians believe the goal and end of the process, leaving all joy out of this life and sole property of the Platonic realm of the hearafter. Some of that joy we find here with us now in the same sense that Aristotle views divinity as being closer to matter than we would like to think. The goal of the abolishment of the soul in Christianity is to free ourselves to align our actions with that of the Spirit glorifying God. Our spirit is in fact the place where our material existence meets with the Holy Spirit, which is dynamic, but the alignment is with the static intentions of the father via means of the Holy Spirit, the so called “plan of God”, and Christ bridges that gap to allow both static and dynamic natures of God as well as man.

What about the bottom right of the ascendent triad? Well this is simply showing that the same is true for another individual (or if you are being orthodox about it, another Christian), and that you are connected to your neighbor via means of the Holy Spirit. This is somewhat profound in that it says that loving your neighbor and loving God are not in fact two separate commandments, but are one in the same, the same basic action. In essensce you are being called to clear up the window of the soul and trace the Holy Spirit back to a mutual point of connection between yourself, others and God. In the words of Alan Watts, another popular secular thinker iconoclast in the Christian world, to stare at another person is to see the face of God staring back at itself.

The final realization is this: In sanctification, we are single natured individuals in intimate relationship with God (or the divine) via means of the Spirit, and that place of intersection we call our own spirit, which only exists in the sense that we find our fundamental struggle as one of overcoming the subjective world of our own mind to objective reality of the world outside ourselves including mankind and God. The tension that conflict creates, we call the Soul or as I prefer to refer to it, the mind. Perhaps returning to the panentheism of Rohr, all of matter is the same way, but we just have a highly developed mind with a will of its own, to stand in its way, a soul stumbling block as it were. Note how this puts man, as a being burdened by the obscuring nature of his own soul, in some ways at the bottom of the hierarchy of being similar to how Neoplatonists understand it.

Note: On reflecting on this section of the blogpost more I realized that its maybe more orthodox to Christianity to say that the goal is not diminishing or abolishment of the soul but rather the refinement of the soul. In this sense man would retain his bipartite or even tripartite nature, after all if I am equating the soul to the mind then we still have a mind and use it to function in daily life. However, from a practical perspective I have experienced that any sort of focusing on the development or refinement of my own soul (i.e. indulging in my own goals and priorities, exercising my will on my own desires), has almost always degenerated into what others (particularly my wife) would consider self absorption. I think in this sense the Buddhist goal of destruction of the ego seems more practical to my lived experience. Perhaps the “true self” as Rohr calls it rises from the ashes of the destruction of the false self like a phoenix, and this same basic impulse to abandon and sacrifice yourself is the Christ-like picture of self sacrifice that we should emulate, trusting that in abandoning our dreams (essentially) to God that he will somehow help us to fulfill them more effectively

I call this the resignation of the soul to the death of the “little self” with the hopeful expectation of ressurection. This is totally regardless to what circumstance may lead you to believe is possible. In this sense, Christ’s ressurection was not just a historical atoning moment, but a template for our posture in life. Resigning yourself to the death of your dreams, no matter how small with the expectation of ressurection of those dreams in a new form is I think the fundamental posture of the Christian life. When asked recently what Christianity meant to me by an atheist, I simply answered the concept or paradigm of ressurection in your daily life. For more on this mindset see the works of Brother Lawrence, or the Little Flower.

Where do we go from here?

What does this mean if this perspective on the trinity is true and biblically founded? I have begun researching this notion more deeply and I am convinced there is further evidence to support it. I’ve also since learned that this is pretty similar to what the Eastern Orthodox church believes, that the Holy Spirit is a more dynamic aspect of God which complements the father and is instrumental in theosis or the Orthodox equivalent of sanctification.

This thesis is fundamentally ecumenical in nature, as it argues that each demination choses to focus on a different aspect of the Trinity as being supreme, the Reformed, Roman Catholic and conservative church on Christ and a Platonic worldview, the progressive Pentacostal and Eastern orthodox church on the Holy Spirit and an Aristotelean worldview, and Judaism and Fundamentalists churches on the Father and the Law. However, I don’t think it has to end there necessarily. I mentioned previously how the new, largely non-tribal perspective on faith imparted to me by writers like Rohr has given me a new approach to even inter-faith dialogue, to the point where I see connections between this new understanding of Christianity and other faith practices. Again, I don’t care about debating (particularly fellow Christians) as to where these ideas originate, whether they are accidental reflections of a Christian God or whether they are wisdom discoveries of their own. That doesn’t matter to me as it amounts to just wanting to validate my own tribe. Whether that makes me universalist, so be it, again I don’t really care but I still find my faith firmly rooted in the Christian traditions, just an expression of faith not so tightly bound to orthodoxy. That said, I can’t help but notice on recently reading the Bhagavad Gita that the basic message, which is to surrender your own ego and ambitions so that you can be more complicit with the Divine will, is identical to the heart of the Christian understanding of sanctification. In a similar way I can’t help but notice that in the above diagram illustrating how the human Spirit is in fact a fingerprint or extension of the Holy Spirit, is similar to the idea of “Atman is Brahman”, and that if you extend this picture out to every individual, you would perhaps be drawing something resembling Indra’s net. I won’t contemplate this further, as to not lose any Christian readers as I’ve found most Christians like to think of Christian wisdom as being esoteric to Christianity, but I just know the next time I find myself in discussion with someone that is from the Vedic traditions about philosophy, I will lead the conversation with these commonalities and not the differences, regardless of what other Christians think of me. I dont say this out of a progressive sense of equity or fairness, but out of a heart of decency, Aristotelian curiousity and awe and respect for the inherit nature of all man which recognizes the potential work of the Spirit within, no matter how latent.

Ultimately a faith thats intimidated by and needs to protect itself from ideas outside of it’s established orthodoxy, and retain that its wisdom is exclusive property of their tradition, is in my opinion, not a very strong one. This does seem call into question Sola Scriptura, but I think at the end of the day I have a much more expansive, perhaps Aristotelian viewpoint on the role of the Spirit in the lives of man. The difference now is that I am free to accept a more Platonic (or even Calvinist) viewpoint on the role of the Father in the Trinity, and I can lean on Christ to keep those two very different worldviews and perspectives of God together as one. Maybe in this sense I can find myself in a position where I am not so antigonistic to a static Calvinistic world view but can be open to integrating it into a more expansive view of God, a complete picture which I find to be intuitively and philosophically more sound.

Could this possibly new theology be the foundation for a new denomination that finally reconciles the differences between the Protestant, Roman and Eastern Catholic churches, as well as Progressive and Conservative churches? Time will tell.

Kyle Prifogle

Twitter Facebook Google+